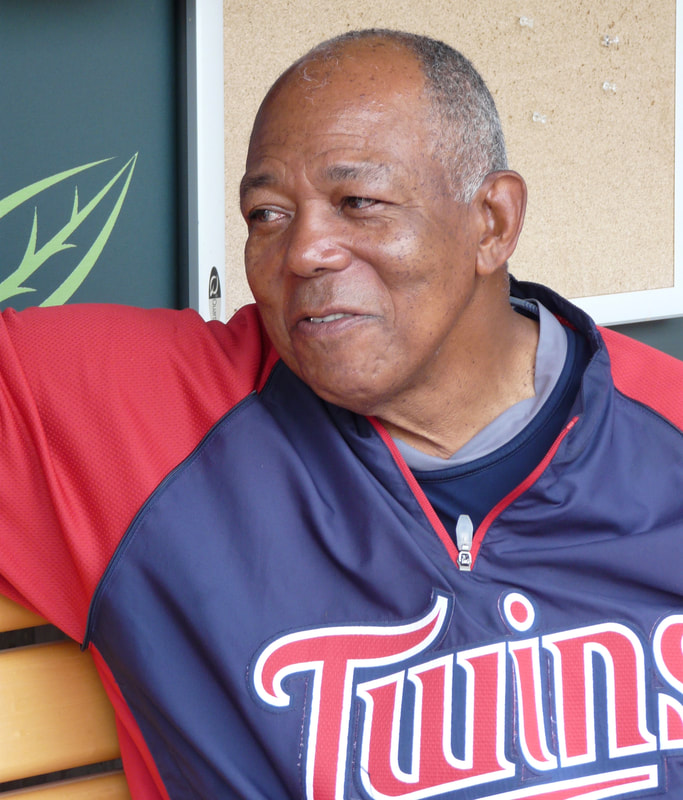

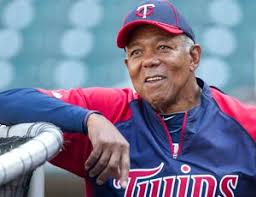

Beginning in 1964, Oliva’s bat ranked with the best for eight seasons before knee injuries left him playing essentially on one healthy leg. Although his power was significantly compromised after blowing out his knee diving for a ball in the in June 1971, Oliva, the pure hitter that he was, still batted .283 over his final three seasons—more than 20 points higher than all AL hitters over those three years (1973-75).

When he was healthy, Oliva hit for average and power. He won three batting titles—1964, 1965, 1971—in an eight-year stretch in which only Roberto Clemente, Pete Rose and Lou Brock averaged more hits per game:

MOST HITS PER GAME (1964-71)

(minimum 3,000 PA)

1.31 Roberto Clemente

1.27 Pete Rose

1.24 Lou Brock

1.23 Tony Oliva

1.19 Curt Flood

Over those eight seasons, Oliva averaged 22 homers a year, a respectable total in a very pitcher-friendly era, but he wasn’t a classic slugger. He drove pitches to all parts of all fields and led all major leaguers in doubles. He ranked third in total bases, and Hall of Famers hold down most of the top 10 spots on the leaderboard.

MOST DOUBLES (1964-71)

278 Tony Oliva

266 Lou Brock

257 Pete Rose

254 Carl Yastrzemski

246 Billy Williams

241 Hank Aaron

229 Brooks Robinson

222 Vada Pinson

222 Rusty Staub

214 Frank Robinson

MOST TOTAL BASES (1964-71)

2,601 Billy Williams

2,542 Hank Aaron

2,356 Tony Oliva

2,288 Lou Brock

2,287 Dick Allen

2,267 Ron Santo

2,249 Roberto Clemente

2,244 Carl Yastrzemski

2,223 Frank Robinson

2,214 Pete Rose

Oliva slugged .507 in those eight years and ranks 10th on a list that features eight Hall of Famers and Dick Allen. Oliva and Allen were the Rookie of the Year winners in 1964, and both fell a single vote short of Hall induction the last time the Golden Days Era Committee met.

Falling short of 2,000 hits stands out when the shortness of Oliva’s elite years is considered. The truth is, the Hall has plenty of members who failed to reach 2,000 hits since the end of the dead-ball era: Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby, Ralph Kiner, Hank Greenberg, Monte Irvin, Roy Campanella, Phil Rizzuto, Tony Lazzeri, Mickey Cochrane, Lou Boudreau, Gabby Hartnett, Rick Ferrell, Freddie Lindstrom, Travis Jackson, Hack Wilson, Earle Combs and Chick Hafey.

Oliva collected 401 hits in his two full seasons prior to suffering his knee injury in June 1971, a month shy of his 33rd birthday. Despite his age, he had been at his best those two seasons, and better health might have produced at least a few hundred more hits and bigger power numbers.

Oliva probably was cheated of a few years on the front end of his career as well. Only one scout worked Cuba in that era and players living much beyond Havana were rarely discovered. Oliva grew up on a remote farm near the west coast of the island—far from Havana—and he was nearly 23 when he was discovered by a former Washington Senators prospect who was from Oliva’s province.

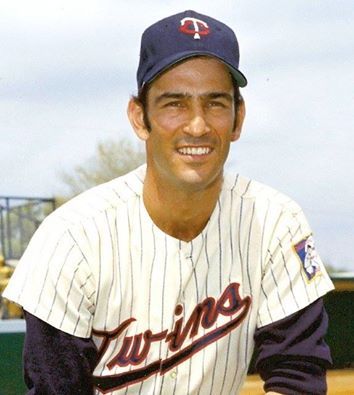

So many of the great pure hitters of his era were on major league rosters by the time they were 21. By that age, Al Kaline, Hank Aaron, Frank Robinson, Joe Morgan, Johnny Bench, Reggie Jackson and Rod Carew were regulars. Because of lack of coaching in Cuba, Oliva’s defensive skills were so raw that he needed three minor league seasons before he emerged to win the AL batting title and Rookie of the Year Award in 1964 at age 26.

The lost time at the start of his pro career was something beyond Oliva’s control, much like Robinson, Doby, Campanella, Irvin, Satchel Paige and many Black stars lost years because the game was segregated—something beyond their control. That comparison of circumstances may not sell voters, but it seems likely that Oliva may have lost at least a few hundred hits at the start of his major league career by virtue of where he was born.

That first batting title was followed by a second in 1965, making Oliva the only major leaguer to ever lead his league in hitting in his first two seasons. The third came in 1971, making him one of only 17 Hall of Fame-eligible players to have won three batting titles in the modern era. Fifteen are in the Hall; only Oliva and Bill Madlock are not.

Somehow Oliva’s stature in the game seems to have slipped over the years. In the nine of the 10 years that Oliva was on the BBWAA ballot along with Bill Mazeroski, he finished ahead of the longtime Pirates second baseman. Likewise, in 11 of the 12 years that Oliva and Ron Santo were on the ballot together, Oliva topped the longtime Cubs third baseman. Both Maz and Santo have been inducted by the Veterans Committee.

“Tony belongs,” Harmon Killebrew told me in a 2009 interview. “You look at certain players who don’t have the stats necessary to get in the Hall of Fame, but during the period they played, they were a dominant player or pitcher. To me, that’s a criterion. Tony was a dominant player in his era. Three batting championships and just over a .300 lifetime average. Just a great, great hitter. He was the best offspeed hitter that I’ve ever seen.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed